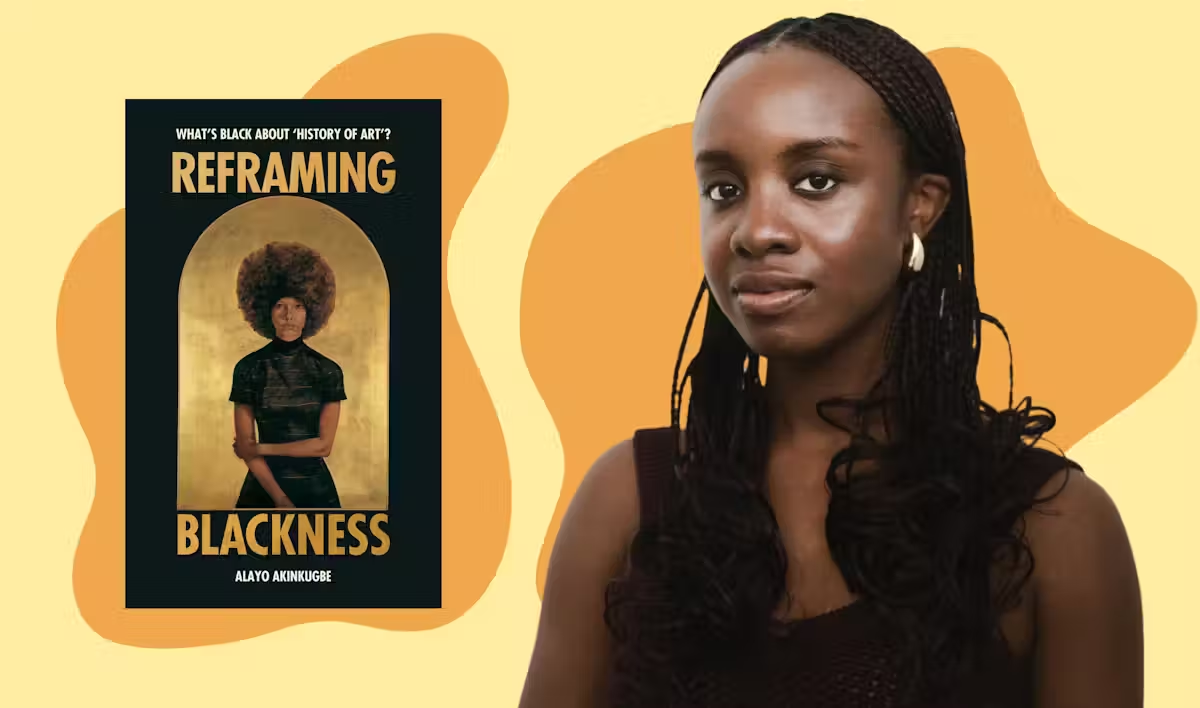

Seeing Blackness First: Author Alayo Akinkugbe’s Challenge to Museums

.jpg)

In her book Reframing Blackness, writer and curator Alayo Akinkugbe offers a powerful call to action for museums and the wider art world: to see blackness first. For too long, the discipline of art history as it is taught in Western institutions, and the exhibitions that follow from it, has systematically pushed blackness to the margins. Akinkugbe’s intervention is both timely and necessary, urging us to shift our gaze and re-examine the structures that define what is displayed, who curates it, and how it is remembered.

Reactive Responses and Surface-Level Commitments

Akinkugbe points out that the scarcity of black curators within major national museums means that blackness is often addressed through “reactive responses.” When George Floyd was murdered in 2020 and protests spread worldwide, art institutions rushed to issue public statements, foreground black artists, and pledge future initiatives. While significant in the moment, these responses were largely temporary, surface-level commitments that failed to alter deeper institutional practices.

As Akinkugbe argues, real change requires structural embedding, long-term shifts in staffing, policy, and collections, not temporary programming that disappears once the headlines fade.

Decolonising the Curriculum

Drawing from her own experience as an art history student at the University of Cambridge, Akinkugbe reflects on the push to “decolonise” curricula. She examines how race, gender, and class intersect in the art world, and highlights the particular double-bind faced by black women, who encounter both racial and gender bias.

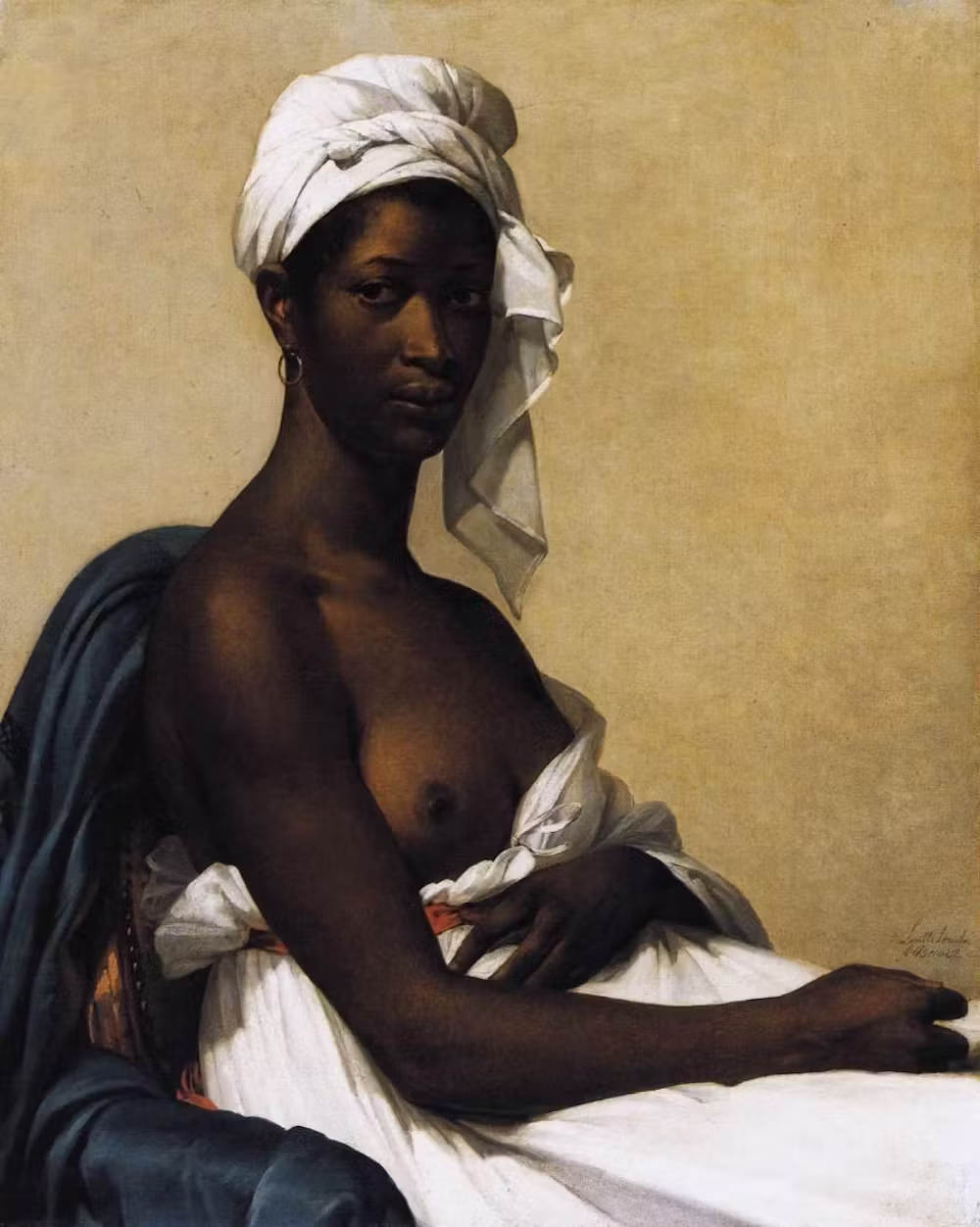

Her call is not abstract: she illustrates what it means to shift the gaze by reintroducing figures of color in historic works. Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une Femme Noire (1800), for example, depicts a black woman who, though present in the canon, has long been overlooked. Similarly, in Jacques Amans’ Bélizaire and the Frey Children (1837), the enslaved child Bélizaire was literally painted out of the picture until conservation revealed his erased presence. Akinkugbe reminds us that these figures were always there, but art history’s dominant frameworks chose to obscure them.

Dialogues With Curators

Akinkugbe situates her work in conversation with leading curators whose exhibitions in recent years have pushed the boundaries of how black life is represented in art. Among them are Antwaun Sargent, curator of The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion; Ekow Eshun, curator of In the Black Fantastic and The Time is Always Now; and the late Koyo Kouoh, whose groundbreaking When We See Us: A Century of Black Figuration was hailed as one of the most important exhibitions of its kind.

By engaging these voices, Akinkugbe underscores that her project is not isolated but part of a larger collective movement committed to uncovering what has been ignored and insisting on blackness as a central, not peripheral, subject of art history.

The Long Struggle for Visibility

Akinkugbe’s book connects with a long trajectory of black cultural activism in Britain, from the Caribbean Artists Movement of the 1960s to the British Black Arts Movement of the 1980s. These movements challenged racial exclusion in the arts and created opportunities for new conversations around justice, visibility, and representation.

The resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 reignited these questions. Institutions pledged to diversify collections, re-examine their histories, and reconsider how curricula addressed colonialism and enslavement. Yet, as Akinkugbe observes, the results are mixed.

Some universities have indeed expanded their geographic focus beyond Europe, or promised to address colonial legacies in hiring. But when budgets tighten, new courses are often the first to be cut. Others risk tokenism, treating Africa, Asia, or the Caribbean as monolithic “global south” modules. Adding black scholars as supplementary readings instead of core texts only reinforces the very marginalisation these efforts claim to redress.

Museums and Responsibility

Akinkugbe insists that museums have a duty to reflect the communities they serve, not merely the elite patrons who founded them. That means ensuring permanent staff reflect diversity across race, gender, class, sexuality, and disability. It also means that directors must see care and accountability as long-term commitments, not optional gestures.

Museums, she suggests, are better equipped to serve their communities when they treat them as partners in shaping the institution’s future. This approach requires listening, humility, and a willingness to confront the uncomfortable histories embedded in museum walls.

Globally

In the United States, leading institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) have faced similar calls to confront their historical exclusions and colonial legacies. In recent years, both museums have pledged to diversify their collections and curatorial staff, while also revisiting how African, Caribbean, and Black American artists are represented in permanent galleries. The Met, for instance, has made efforts to integrate African art into broader narratives of global art history rather than confining it to isolated departments, while MoMA has foregrounded exhibitions highlighting Black abstraction and diasporic creativity. These efforts signal a recognition that blackness cannot remain peripheral in institutions claiming to tell a global story of art.

Yet, as with their European counterparts, questions of permanence and sincerity remain. Critics argue that many of these initiatives are still framed as temporary projects responding to moments of social pressure, such as the widespread protests of 2020, rather than as structural shifts embedded into museum governance. Hiring practices, acquisitions policies, and board compositions often lag behind public commitments, raising doubts about whether real transformation is underway. The experiences of the Met and MoMA reflect the broader global challenge: moving beyond reactive gestures toward systemic change that acknowledges blackness as integral to art history rather than an add-on to appease contemporary demands.

Across Africa, museums such as the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) in Cape Town have positioned themselves as leaders in re-centering black and African narratives within contemporary art. Since its opening in 2017, Zeitz MOCAA has dedicated itself to showcasing the work of African and diasporic artists, with exhibitions that foreground lived experiences of race, identity, and history. Its curatorial approach challenges Eurocentric hierarchies by treating African creativity as the primary lens through which the global art story can be told, rather than a secondary or “regional” contribution. In doing so, the museum has become a vital counterweight to the legacies of exclusion in Northern institutions.

In the Caribbean, institutions such as the National Gallery of Jamaica and the National Art Gallery of The Bahamas have also worked to embed blackness as central to cultural heritage and artistic production. These museums not only preserve and promote the work of local artists but also serve as spaces for critical engagement with histories of slavery, colonialism, and independence. Exhibitions frequently connect past and present, linking traditional art forms with contemporary practices that interrogate identity and belonging. By doing so, Caribbean museums provide models of how cultural institutions can be rooted in the communities they serve while addressing global questions of representation and equity.

Cautious Optimism

Reframing Blackness offers both critique and cautious optimism. Akinkugbe is clear-eyed about the systemic barriers to change, yet she also points to the progress that has been made: exhibitions that challenge assumptions, educators who expand syllabi, and younger generations who refuse to accept exclusion as inevitable.

Her book asks us to see blackness first, not as an afterthought, not as a corrective, but as a fundamental presence in art’s past, present, and future. This vision does not require black people to reinsert themselves into the narrative. It insists that blackness has always been there, waiting for the art world to reckon with its resolute presence.

Credit: This article was written by Wanja Kimani, Associate Curator at The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, and originally published in The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.