Minister: New Nature Policy Plan Merges Policy and Action Plan Into One Document

.jpg)

GREAT BAY--Minister of Housing, Spatial Planning, Environment and Infrastructure (VROMI) Patrice Gumbs on Friday presented a technical outline of the new draft Nature Policy Plan 2025-2030 and positioned it as both a legal requirement and a national roadmap for how St. Maarten will protect biodiversity over the next five years. He said the updated plan is designed to meet local obligations under the country’s nature management legislation while aligning with the UN Convention on Biological Diversity and the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, the global set of targets guiding biodiversity action through 2030.

In his presentation, the minister framed the updated plan as both a national requirement under local law and an international obligation tied to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). He also acknowledged a recurring local frustration that surfaced repeatedly in questions from Members of Parliament (MPs): residents want to know what this plan changes in daily life, how enforcement will improve, and whether VROMI has the staffing, legal tools, and budget to deliver what the document promises.

What the Nature Policy Plan is, and why it comes to Parliament

Minister Gumbs said the legal requirement for a nature policy plan is rooted in the National Ordinance on the Foundation of Nature Management and Protection, citing Article 2 as the basis for the minister to establish a national nature policy plan that also implements international obligations. He also referenced Article 9 as part of the domestic framework requiring a “nature plan,” which he described as the implementation plan that outlines tangible actions and timeframes.

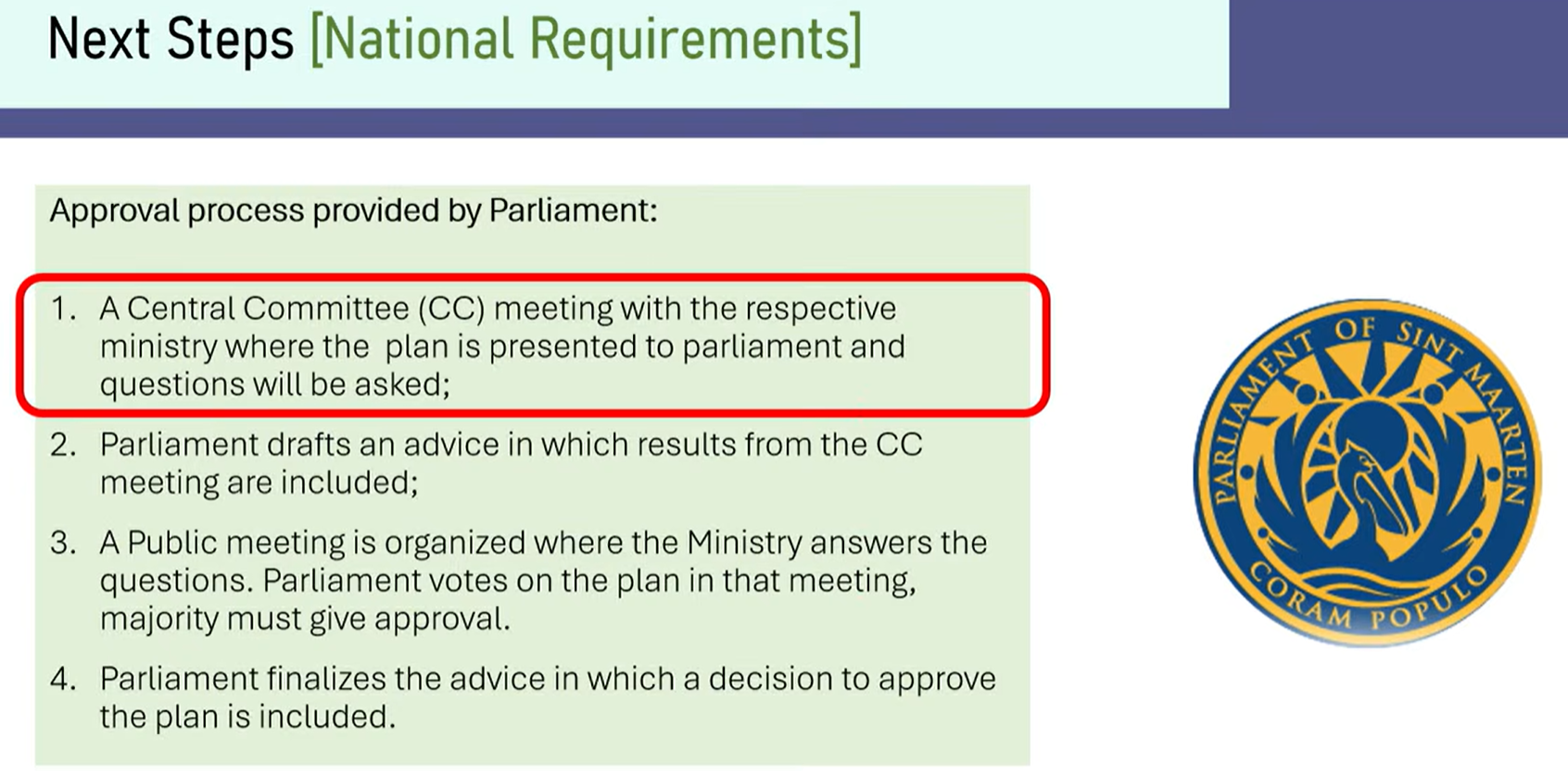

He flagged an issue he said the ministry intends to address in an upcoming review of the ordinance. Based on the ministry’s interpretation, the law’s wording around parliamentary approval appears inconsistent, and may reflect a legislative carryover issue dating back to the constitutional transition of 10/10/10 and earlier governance arrangements. The minister told Parliament the ministry plans to launch an assignment to review and update the ordinance, including the relevant article(s).

International obligations, and the shift to the Global Biodiversity Framework

The minister explained that the plan is also St. Maarten’s national response to the CBD, which the Kingdom of the Netherlands has been party to since 1994, with St. Maarten included since 1999 through the former Netherlands Antilles arrangement. Under the CBD, countries are called on to develop National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs), which set national direction for biodiversity protection and management.

He told MPs that the global framework has evolved. The earlier Aichi Biodiversity Targets (2011–2020) were followed by the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), adopted in December 2022, which sets 23 targets to be achieved by 2030. Minister Gumbs said countries were expected to revise, update, or develop their national plans to align with the GBF and submit them before the next CBD reporting cycle.

Because the Kingdom is a single party to the CBD, he said NBSAPs are still required for distinct parts of the Kingdom, including the European Netherlands and the Caribbean countries, reflecting different ecosystems and implementation realities. In that context, St. Maarten’s Nature Policy Plan 2025–2030 is being treated as the country’s NBSAP.

To illustrate the GBF, the minister highlighted several targets he said are particularly relevant locally, grouped in three clusters:

- Reducing threats to biodiversity: reducing impacts of invasive species, reducing pollution risks, and minimizing climate change impacts on biodiversity.

- Meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit-sharing: restoring and maintaining nature’s contribution to people, including ecosystem functions, and improving health and well-being through biodiversity-inclusive planning.

- Tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming: integrating biodiversity into policies and planning, building public-private partnerships and mobilizing resources, and improving availability of and access to data.

A major portion of the minister’s remarks focused on setting scope. He said the nature policy plan does not cover the “gray” environmental subjects typically associated with waste management, energy, soil pollution, and water quality, even though those issues directly affect nature outcomes.

He described “nature” as addressing the “green and blue” subjects: species protection, habitat conservation, monitoring and management of protected areas, and direct threats to biodiversity. Because the two spheres are linked, he said the ministry intends to complement the Nature Policy Plan with a separate Environmental Policy Plan, while emphasizing that the only formal legal requirement outlined in law is for the nature policy plan.

Looking back: the 2021–2025 plan, and why implementation lagged

Before turning to the updated plan, Minister Gumbs summarized the previous Nature Policy Plan (2021–2025), which contained nine overarching policy objectives. He said the plan was drafted from work that had been underway since 2016 and was developed through stakeholder consultation before being finalized in 2021. He attributed delays to staff turnover and the disruption caused by Hurricane Irma, and noted that the plan underwent a one-month public review period during which community feedback was received and incorporated.

He also outlined why parliamentary approval did not occur during the previous cycle. Following public discussion and a Central Committee meeting in April 2024 on implementation status, MPs raised queries that needed written responses. The then minister requested a two-week timeframe to respond, but parliamentary elections and a change of government interrupted the follow-up process, leaving the plan without formal parliamentary approval and limiting structured reporting on implementation.

On progress, Minister Gumbs acknowledged the ministry found implementation “slower than originally hoped,” citing human capacity constraints, COVID-era impacts, limited operational budget, and the complexity of securing external financing. He said the updated plan therefore carries forward activities that were not completed under the previous cycle.

The updated Nature Policy Plan 2025–2030, what changed, what stayed the same

The minister said the updated plan was developed with support from the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature (LVVN) under a cooperation framework involving St. Maarten’s VROMI and TEATT ministries, Aruba, and Curaçao. He said external consultants supported drafting, and that the work was partly motivated by the reality that, while each country has its own plan, the Kingdom remains a single party under the CBD.

He also told MPs that the broader cooperation MOU has faced implementation delays tied to political developments in the Netherlands, and that some planned actions under the MOU were paused.

A key finding, according to the minister, was that St. Maarten’s existing policy framework already aligned strongly with the GBF and the standardized NBSAP outline. The areas identified as needing the most strengthening were implementation planning and institutional monitoring and reporting.

He emphasized that the updated Nature Policy Plan 2025–2030 is largely unchanged from the previous plan. Still, he listed several structural updates:

- The Nature Policy Plan and the Nature Plan (action plan) were merged into one document.

- A new Chapter 4, “Ensuring effective implementation,” was added.

- Actions and timelines were updated, and additional actions were included to align with the GBF.

- Some actions within policy objectives were reorganized.

He showed a contents overview with six sections, plus an appendix action plan: Introduction; Strategy (vision, principles, objectives); Action Plan; Ensuring effective implementation; Monitoring and evaluation; Concluding remarks; Appendix 1.

The plan’s vision, and its nine policy objectives

Minister Gumbs said the plan’s vision is unchanged: a shift in attitude toward seeing nature not as a barrier to development, but as an essential national asset that supports economic well-being, strengthens resilience to natural disasters, and supports human well-being.

The updated plan retains nine policy objectives, with minor wording adjustments to two objectives while keeping the same intent. The objectives presented to Parliament were:

- Increased conservation, restoration and management of biodiversity.

- Improved research and monitoring to provide an evidence-base for effective policy.

- Increased sustainability and resilience of the tourism sector.

- Increased communication, education and public awareness of nature.

- Legislative improvements to reflect current situation, with effective enforcement.

- Nature integrated into development strategies.

- Increased local, regional and international cooperation for nature.

- Sustainable financing for nature.

- Climate Change integrated into national planning and nature harnessed for adaptation.

What the minister listed as outputs, and achievements so far

In walking MPs through the plan, Minister Gumbs explained that each objective is supported by intended outcomes and outputs. Outputs are meant to be measurable steps within timelines, designed to deliver the broader outcomes and, eventually, the plan’s vision.

Among the examples he cited:

- Under Objective 1, he described work such as developing an island-specific Red List, strengthening protected areas and enforcement, improving controls around sensitive species, joining the Dutch Caribbean Marine Mammal Sanctuary, establishing invasive species management plans, and integrating principles to reduce pollution impacts into policy. He cited as achievements steps involving the Nature Foundation, work toward the marine mammal sanctuary, increased funding to the Nature Foundation to support invasive species management, and ongoing updates to environmental norms.

- Under Objective 4, he emphasized education and awareness, pointing to Project Karina’s outreach component led by the Nature Foundation, a mangrove protection project, and a collaboration involving conch shell awareness. He also spoke about improving public access to information through websites and data platforms, and referenced the Climate Impact Atlas for St. Maarten as a tool that includes nature and environment-related geospatial information.

- Under Objective 6, he said priorities include strengthening geospatial data availability for planning, integrating nature values into urban planning, moving toward mandatory Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) for select developments, and strengthening permit processes, including through procedure manuals and updated norms to support the hindrance permit process.

- Under Objective 8, he focused on the financing gap. He said a National Biodiversity Finance Plan is being developed with support mobilized through LVVN, with Grant Thornton involved in drafting a national biodiversity finance framework. He also referenced increased budget allocation to the Nature Foundation as part of strengthening implementation capacity.

- Under Objective 9, he described work on climate data collection, procurement of weather stations, publication of climate scenarios for St. Maarten, the Climate Impact Atlas, and ongoing drafting of a national climate change adaptation report and strategy, alongside ecosystem-based adaptation planning.

Chapter 4: “Ensuring effective implementation,” the plan’s hard reality section

The newly added implementation chapter, the minister said, begins by acknowledging that the plan is ambitious and difficult. He told Parliament that implementation will require coordination and realism, and that the ministry wants to be explicit about enabling conditions that must be in place before actions can succeed.

He identified four major enabling conditions the plan prioritizes:

- Government capacity

- Sustainable funding and investments, and the supporting legal and data framework

- Shared values for development in harmony with nature

- A strong coordinating structure

The chapter presents priority actions meant to advance these enabling conditions, effectively treating them as prerequisites for delivery.

Monitoring, reporting, and international deadlines

Minister Gumbs said progress would be measured through output and effect indicators, while acknowledging that effect indicators can be difficult due to qualitative impacts and limited baseline data. The plan, he said, anticipates annual reviews to assess budgets, activity schedules, and whether updates are needed as capacity changes.

He also outlined the international reporting track:

- The plan, once nationally approved, must be submitted through LVVN for upload to the CBD online reporting system, where it becomes publicly accessible.

- The CBD does not “approve” or “reject” an NBSAP, but may check for completeness and clarity.

- National reports are submitted every four years, and the 7th National Report is due February 28, 2026, which he said is the first report under the GBF and is proving complex internationally.

- A biodiversity finance plan is tied to GBF Target 19(b), emphasizing increased domestic resource mobilization and national financing instruments.