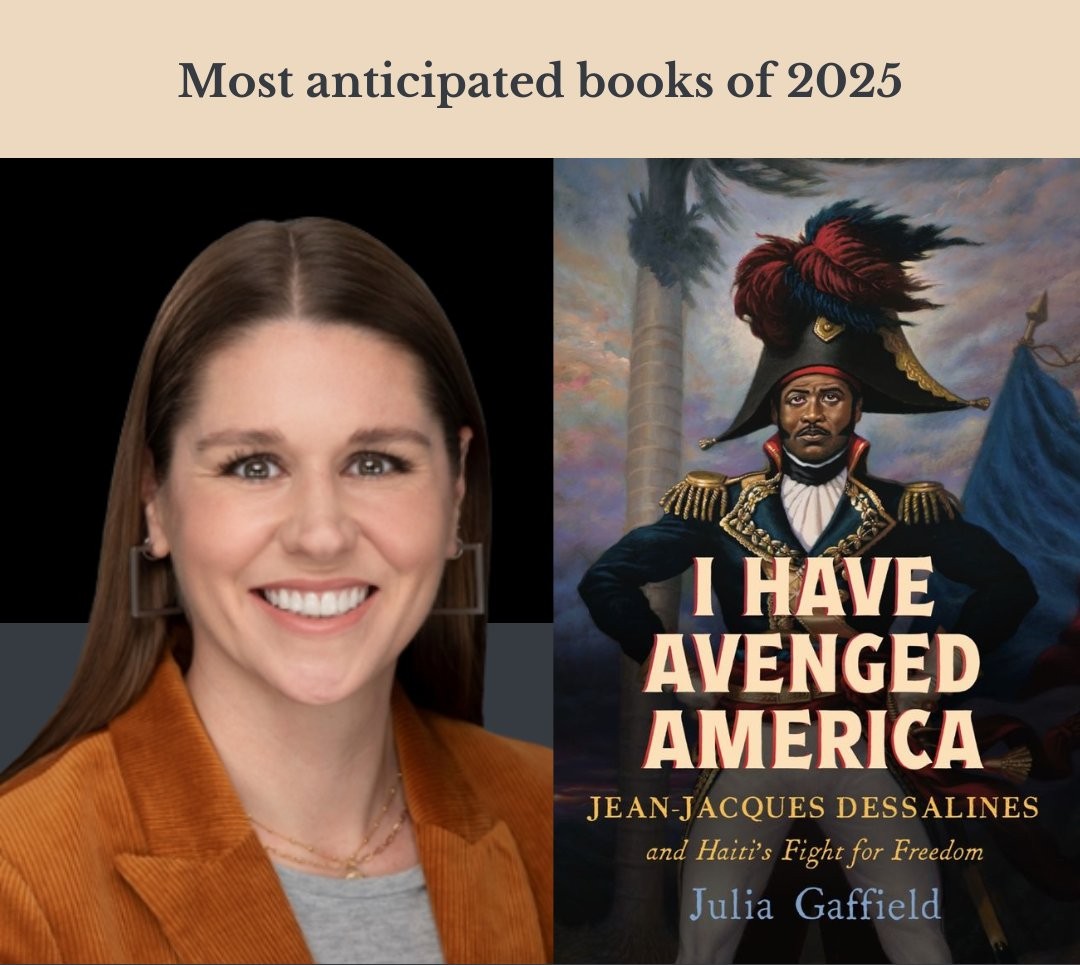

A new book about Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and why his record still divides to this day

Author Julia Gaffield has released a new book, “I Have Avenged America: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti’s Fight for Freedom,” a reassessment of the Haitian revolutionary leader’s role in ending slavery and founding the first Black republic. Drawing on new research and a wide archival record, Gaffield presents Dessalines as commander, author of independence, and head of government, inviting readers to weigh his choices within the realities of invasion, forced labor legacies, and international isolation.

The book positions Dessalines at the center of Haiti’s transition from war to statehood, clarifying the independence proclamation of 1804, the 1805 constitution, and the policies that followed. It addresses why English-language narratives often narrow his legacy to a single episode, and explains how that reduction shaped public understanding for two centuries.

For Caribbean readers, the book offers a framework to teach and discuss emancipation, sovereignty, and debt. It links Haiti’s experience to regional debates on historical memory, external pressure, and small-state diplomacy. “I Have Avenged America” is intended for scholars, educators, and general readers, providing a clear account of Dessalines’ record and its relevance to the present.

A feature article about the book via theconversation.com presents Gaffield's book's core claim: the English language conversation has treated Jean-Jacques Dessalines as a secondary figure, while Haitian sources and on the ground memory place him at the center of the revolution’s endgame and the state’s founding. The article functions as a précis of the book, it lays out the terrain Gaffield covers, the military campaign after Toussaint Louverture’s capture, the independence act of 1804, the 1805 constitution, and the political fractures that followed. The aim is not to replace one hero with another, it is to restore the scope of Dessalines’s leadership and to ask readers to weigh his choices in the context of invasion, enslavement, and isolation.

First, the book signals new archival work and synthesis in English, a space where Haitian and Francophone studies have long been underused. Second, it puts method at the center, who wrote what, which records survived, which voices circulated in Britain, France, and the United States, and how those routes shaped what students and the public learned. By setting those questions out front, Gaffield invites a reading that checks sources, compares editions, and watches how labels move from politics into history.

What the reassessment adds

Gaffield reconstructs Dessalines in three linked roles, commander, founder, and head of government. As commander, he led the final campaign that forced the French expedition to withdraw, a shift from stalemate to exit. As founder, he declared independence and defined Haiti as a refuge for the formerly enslaved, a state that would not return to plantation slavery. As head of government, his tenure was short and contested, yet it fixed key lines, no restoration of slavery, resistance to recolonization, and a claim to equal status among nations. Placed together, these roles show continuity of purpose through fast changing conditions.

The feature stresses how a few episodes have dominated Anglophone narratives, especially the 1804 killings of remaining French colonists. The book asks readers to hold two facts at once, the war’s mass violence and the emancipatory result, freedom secured by people who had been enslaved. That framing does not excuse abuses, it restores proportion, the French campaign to reinstate slavery after 1794, the deportation of Louverture, the scorched war that followed, and the hard choices of creating a state in ruins.

Context and constraint

The reassessment places Dessalines inside a hostile Atlantic system. External recognition was scarce, credit was scarce, invasion threats were real. Later, the 1825 indemnity demanded by France, and the refinancing that followed, deepened fiscal strain and isolation. These constraints shaped policy debates on land, labor, and security. Reading Dessalines with those constraints in view allows a fairer test, one that compares him to leaders who governed under siege rather than to peacetime reformers with allies and markets.

Why this matters for Caribbean readers

Caribbean states face related questions, how to teach violence in the making of freedom, how to describe policies taken under external pressure, how to judge leaders who governed with limited choices. A careful reading of Dessalines helps set a regional frame, one that links Saint-Domingue to emancipation timelines in Jamaica and Barbados, to French Caribbean struggles over status, to Dominican-Haitian relations on a shared island, to later debates about debt and sovereignty. It also supports curriculum updates, many syllabi still center British and French abolition, while treating the Haitian Revolution as a sidebar. Gaffield’s work helps rebalance that story, it shows a Black republic declaring freedom for itself, and forcing empires to confront a new fact.

Reading Dessalines with care

A sound reading will avoid two traps, hagiography and reduction. It will treat Dessalines as a political actor who made choices under threat, it will examine how those choices affected freedom, property, and security, it will compare him to contemporaries who faced similar constraints, and it will trace how later writers recast him to fit their own arguments. That method supports better history, it also protects public debate from easy analogies and quick labels.

Gaffield’s published feature, anchored in her new book, asks readers to see Dessalines as founder in full. Commander who finished a war, author of independence who set a moral floor, head of government who operated inside a hostile world. That composite does not end the argument, it improves it. For the Caribbean, a clearer Dessalines strengthens teaching, commemoration, and diplomacy. It gives policy makers and citizens a better base when they think about freedom, security, and the price small states pay to defend both.

𝘊𝘳𝘦𝘥𝘪𝘵: 𝘛𝘩𝘪𝘴 𝘢𝘳𝘵𝘪𝘤𝘭𝘦 𝘥𝘳𝘢𝘸𝘴 𝘰𝘯 𝘑𝘶𝘭𝘪𝘢 𝘎𝘢𝘧𝘧𝘪𝘦𝘭𝘥’𝘴 𝘧𝘦𝘢𝘵𝘶𝘳𝘦 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘛𝘩𝘦 𝘊𝘰𝘯𝘷𝘦𝘳𝘴𝘢𝘵𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘪𝘯𝘵𝘳𝘰𝘥𝘶𝘤𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘩𝘦𝘳 𝘣𝘰𝘰𝘬 “𝘐 𝘏𝘢𝘷𝘦 𝘈𝘷𝘦𝘯𝘨𝘦𝘥 𝘈𝘮𝘦𝘳𝘪𝘤𝘢: 𝘑𝘦𝘢𝘯-𝘑𝘢𝘤𝘲𝘶𝘦𝘴 𝘋𝘦𝘴𝘴𝘢𝘭𝘪𝘯𝘦𝘴 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘏𝘢𝘪𝘵𝘪’𝘴 𝘍𝘪𝘨𝘩𝘵 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘍𝘳𝘦𝘦𝘥𝘰𝘮,” 𝘢𝘯𝘥 𝘦𝘹𝘱𝘢𝘯𝘥𝘴 𝘵𝘩𝘦 𝘥𝘪𝘴𝘤𝘶𝘴𝘴𝘪𝘰𝘯 𝘧𝘰𝘳 𝘢 𝘊𝘢𝘳𝘪𝘣𝘣𝘦𝘢𝘯 𝘢𝘶𝘥𝘪𝘦𝘯𝘤𝘦.